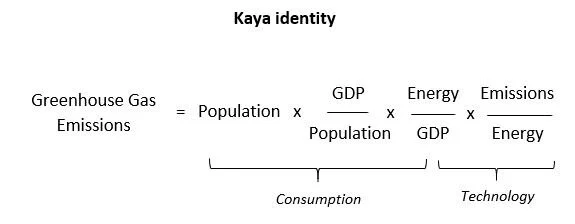

Mitigation and the Kaya identity

In this post from the book NET-ZERO:

What are the three possible strategies for dealing with climate change? The benefits and risks of adaptation, climate engineering, and mitigation strategies.

What is the Kaya identity? Breaking down the growth of greenhouse gases between population, consumption, efficiency, and emissions intensity.

What are the most effective ways to eliminate emissions? Why population controls are ineffective, curbing consumption is useful but culturally challenging, efficiency improvements are great but only slow change, and why net-zero technologies are needed for a complete solution.

Dealing with Climate Change

We have three ways of dealing with climate change; adaptation, climate engineering, and mitigation, here is what each strategy requires:

Adaptation involves preparing and adjusting to climate changes in the future. With nearly 1.5⁰C of warming already locked-in we must continue to adapt and prepare for a warmer planet through measures like building cooling shelters, developing drought resistant crops, and building sea-walls. However, choosing adaptation as the only strategy and letting emissions of GHG gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere risks potentially unmanageable change and dangerous tipping points. Other action is also needed.

Climate engineering falls into two categories, Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and Negative Emissions Technology (NET). SRM strategies are proposed techniques which could be used to block or reflect the sun’s energy before it is absorbed by Earth. This could involve using space mirrors, cloud whitening, or injecting sulphur into the upper atmosphere - these measures are cheap, scalable, and should limit warming but they don’t solve ocean acidification or air pollution, and run seriously high risk of either failing to work or falling victim to terrorist attack or geo-politics.

Negative Emissions Technologies work by drawing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it - these measures range from cheap, effective, but limited scale options like planting trees to complicated engineering solutions like direct air capture technology which is flexible and scalable, but expensive. NET will likely play some role in reaching net-zero, and will be particularly useful for offsetting the emissions in areas of the economy which prove difficult to eliminate.

Mitigation is our third and final strategy which, unlike adaptation or climate engineering, assumes prevention is better than cure. Mitigation is the process where we make the necessary changes to reduce and eventually eliminate ongoing greenhouse gas emissions. This slows and eventually stops the accumulation of CO2e in the atmosphere which in turn slows global warming and ocean acidification to within safe limits.

Mitigation and the Kaya Identity

But how do we begin to choose the best route to mitigate greenhouse gases? To better understand our options, we can use something called the Kaya identity. The expression simply states that emissions of greenhouse gases are the product of the population, GDP per person, energy efficiency, and emissions intensity.

Over the last fifty years annual CO2e emissions have increased nearly 2.5 times, rising at the same speed as population. However, break the contribution down into the elements of the Kaya identity and you quickly realise that emissions would have grown even faster than population (with consumption rising 4.5x per person) if it weren’t for large improvements to efficiency and a gradually declining emissions intensity.

So, which of our Kaya identity levers will be the most effective route to mitigating worse case climate outcomes in the future?

Population and consumption have continuously gone the wrong way. Energy efficiency has been the biggest offset but has physical limits to improvement. Declining carbon intensity has proven only a small offset so far, but it is the only solution capable of reaching zero emissions.

Well let’s take a simple climate model and pull each lever to get a better understanding.

Testing the Kaya Identities

In a world of exponential consumption with 10 billion people consuming 2% more every year but with no improvement to technology, then global warming could reach 10⁰C by the year 2200. This will serve as our simple benchmark.

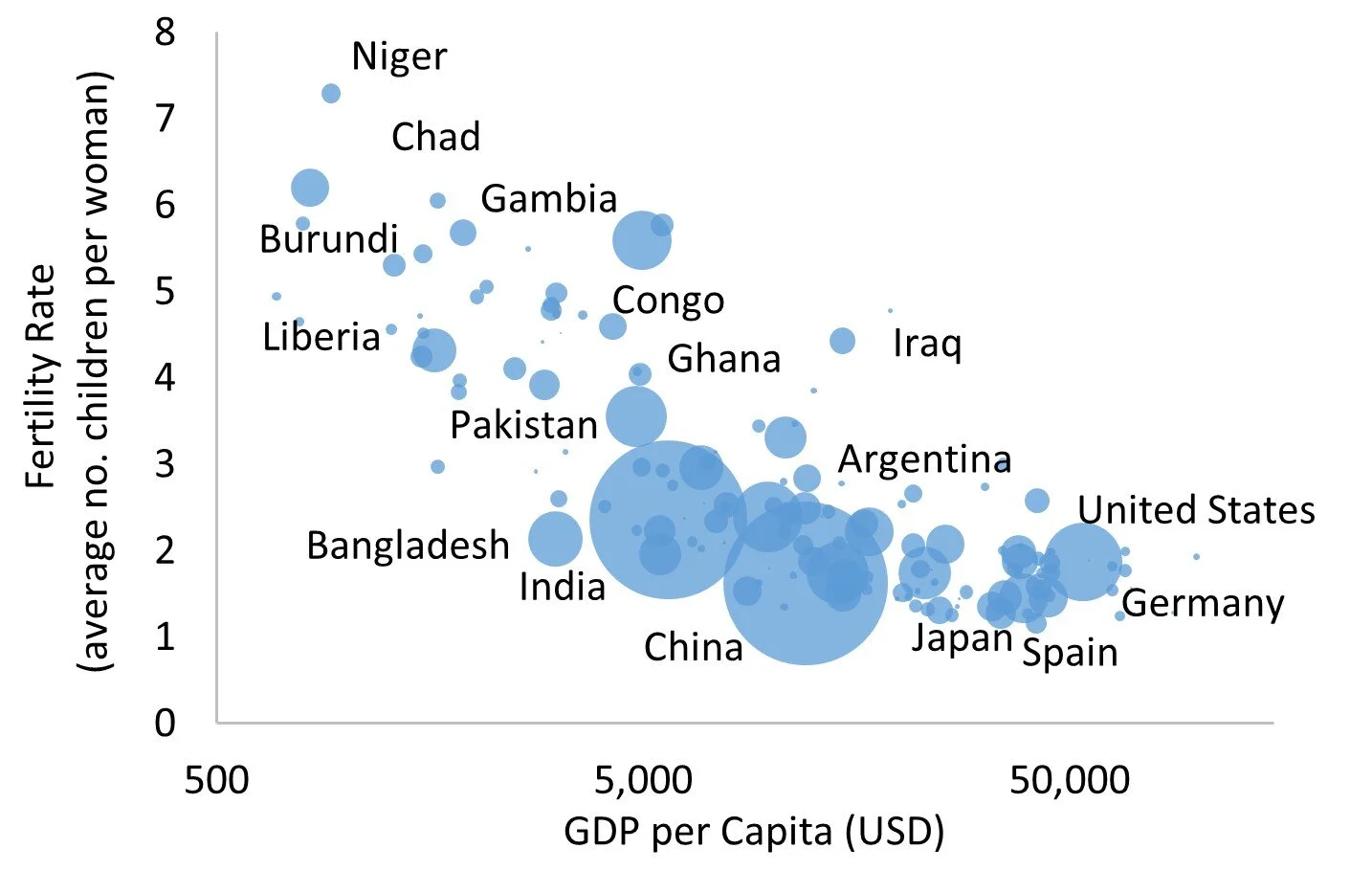

First let’s look at population growth. Statistics show that the number of children a woman will bear over her life is not a function of culture or religion but most closely correlated with wealth. Rising incomes create better education, health, nutrition, social care, and the potential for greater equality, thus reducing the risk of child mortality and the need for extra labour or social care in later life. So as long as the money finds its way to those that need it, fertility rates will begin to decline about one generation after incomes begin to increase.

Wealthy countries already have stable population numbers and, if the wealth of poorer areas of the world continues to rise, then more families will climb into the middle-income brackets where reproductive rates rapidly drop towards two children (above $5,000 income) and populations stabilise. The world is already nearing peak children with two billion below the age of 15 and the United Nations estimates a global peak population of between 9 and 13 billion people by the end of this century.

But what if we could speed up the process? How effective is population control for avoiding disastrous climate change outcomes? Historically, direct intervention has proven ineffective and is fraught with moral dilemmas. But for a moment let’s ignore the moral and practical implications and simply assume that from now on each woman in the world bears just one child. The population would decline to around four billion (from eight billion today) by the start of the next century, emissions would decline proportionally and, because of the decrease in food demand, nearly half of all agricultural land could be reforested. This would slow warming, but if each remaining person continued to increase consumption at 2% per year, the difference would be slight. Emissions would still climb to hundreds of billions of tonnes CO2e per year (from 50 billion today) and temperatures would still reach 6-7⁰C higher by the year 2200.

Okay, so if direct population control is ineffective, and population will limit itself anyway, then maybe setting a limit on consumption might be the better idea?

We could reduce today’s average global income by one quarter and distribute the wealth evenly across the planet. Everyone lives on $14,000 per year income and for the top 10% this means reducing our demand by driving less, flying less, heating or cooling our homes less, buying less, and switching expenditure to lower emissions goods and services. Assuming no further improvements to technology, this action could hold emissions flat. The planet would still warm 4⁰C by the end of the next century. Better than population controls, perhaps, but we still risk dangerous tipping points and widespread damages.

What about technology? Can we go on exponentially consuming more goods and services but rely on markets and technology to become more efficient? Energy efficiency has been the biggest emissions offset for the last fifty years; in fact, we have improved efficiency by 1-2% per year. The fundamental basis for efficiency improvements is to maximise the conversion of energy to useful work rather than wasteful work, and to reduce waste resources as we produce goods, food and services. However, even if we project continued efficiency improvements long into the future, emissions eventually increase 2-3 times over with accompanying warming of 5⁰C by the end of the next century.

That leaves carbon intensity. What if we switched to zero emissions production of energy, goods and services over the next 30 years whilst still letting consumption grow exponentially?

We could replace fossil fuel energy with net-zero emissions energy from renewables, fossil fuel with carbon capture, or nuclear. We could transform our appliances to run on that net-zero energy. Assuming emissions from transport, industry, and basic amenities could reach net-zero in three decades, while emissions from the use of agricultural land continues until peak population & peak food consumption, then global warming would be limited to 2.5⁰C. The best single option it would seem, but still one that risks dangerous tipping points.

The Path of Least Resistance

There is no single lever in the Kaya identity which keeps global warming below temperature thresholds that risk unmanageable change. Population control is too slow, morally difficult, and practically challenging; and as Nobel laureate Amartya Sen writes in ‘Development as Freedom’, “The solution of the population problem calls for more freedom, not less”, improve the lives of the poorest and population will reach a natural limit.

Limiting consumption is perhaps a better option but will always leave residual emissions and it requires enormous economic, political, and cultural transformation.

Energy efficiency has proven the biggest offset to date, but efficiency improvements decline exponentially with physical limits and will always become overwhelmed by uncapped exponential consumption increases.

Cutting emissions intensity to zero through technological change is the closest we come to a low-risk solution, but 30 years is faster than any energy transition in history (50-100 years) and without the accompanying changes to agricultural practices, land management, and food consumption, dangerous limits will still be breached.

The path of least resistance will use a combination of all the Kaya levers to create an optimal mitigation solution. Population should self-limit with increasing wealth. Energy efficiency trends must accelerate to buy us more time. Consumption reduction is required in areas such as meat consumption. Reducing emissions intensity provides full decarbonisation.

Mitigation using all levers of our Kaya identity provides the only complete and low risk strategy to avoid the worst impacts of climate change and eliminate air pollution. A rapid transition to net-zero creates the best possible economic, social, and environmental outcome.